Celebrating 75 Years: The Early Work of JAARS in South America

This article is the first in a three-part series about the early days of JAARS in South America, in conjunction with our celebration of 75 years of God’s faithfulness.

Why Doesn’t Your God Speak My Language?

The seeds for JAARS, Wycliffe Bible Translators, and SIL were planted in Central America.

During World War I, William Cameron Townsend felt convicted by a female mission worker who urged him to sell Bibles in Guatemala rather than serve in the military.

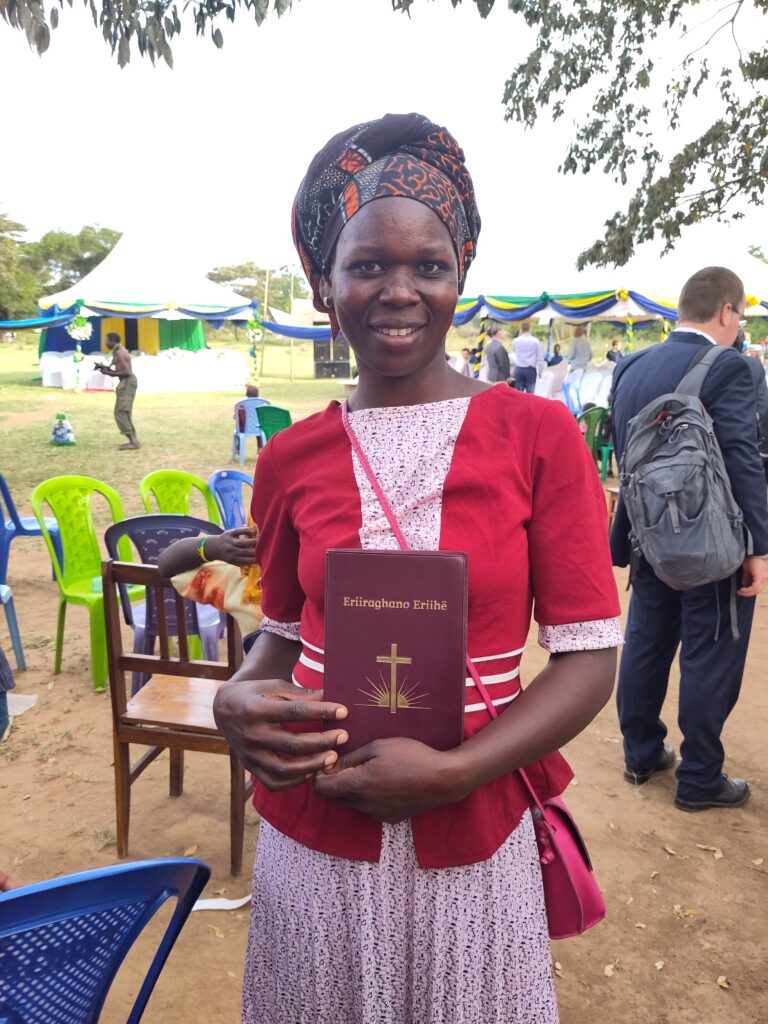

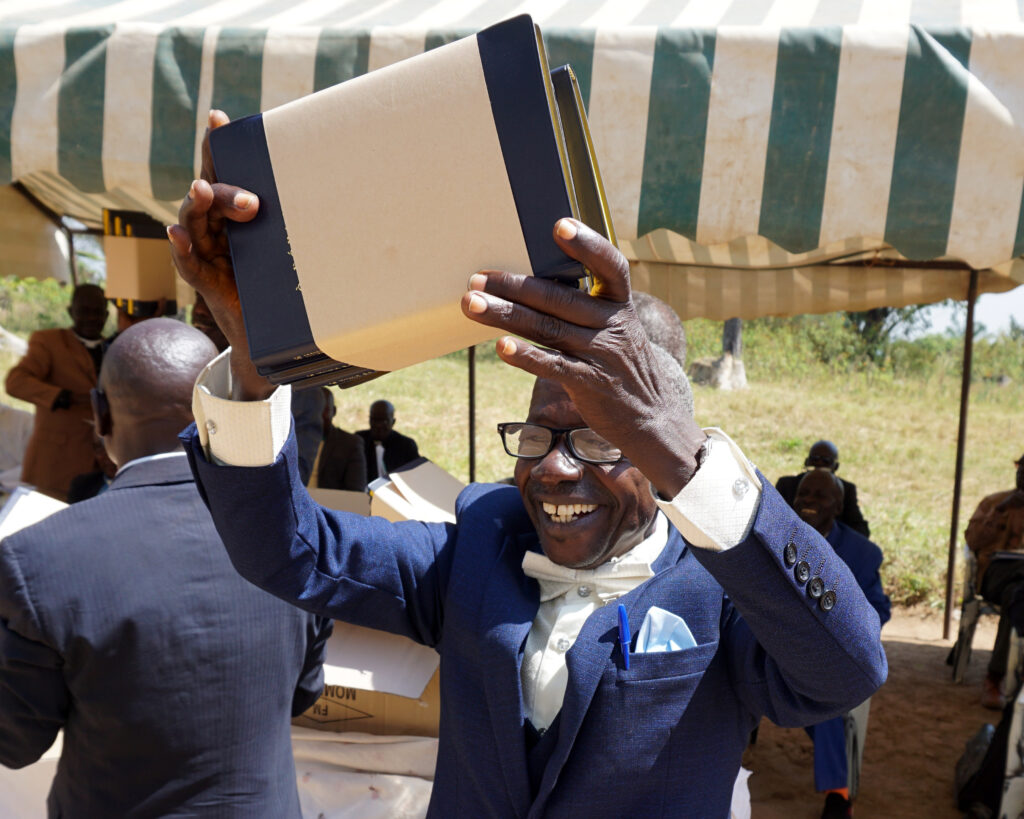

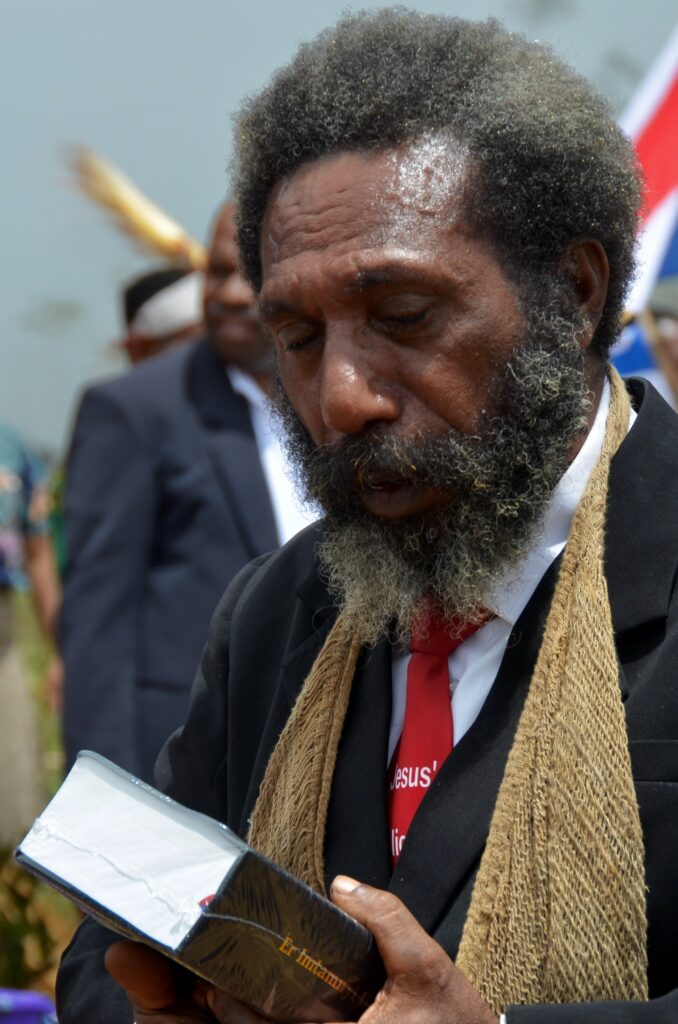

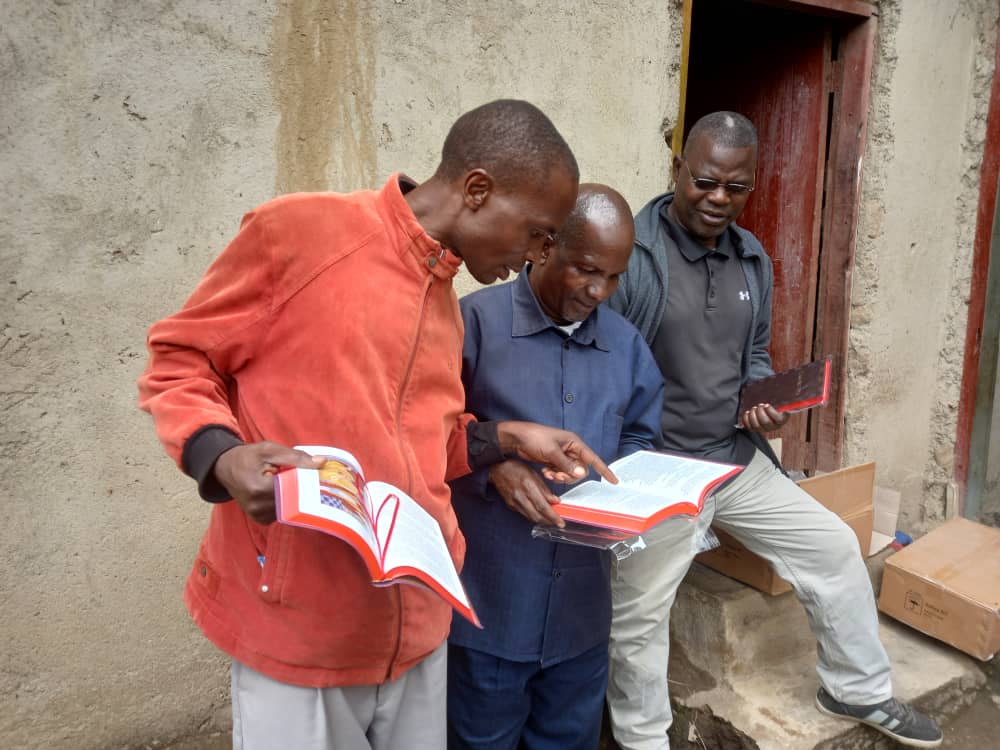

While Cameron was trying to sell Spanish Bibles to a people group called the Cakchiquels, they sometimes asked him why God didn’t speak their own language instead of Spanish, which they rarely spoke and couldn’t read or write.

So Cameron spent the next 10 years translating the New Testament into Cakchiquel, and the vision for translating God’s Word into the language of the people was born. He also served the people by instructing them on health and nutrition.

By 1934 Cameron realized that he needed trained linguists to translate Scripture, so he organized a summer training camp in Arkansas with two students. This effort became the beginning of the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL).

His sensitivity to people’s physical and spiritual needs impressed a Mexican dignitary who saw Cam’s work in Guatemala. The man invited him to do the same work in Mexico, and several students went there to translate the New Testament.

In 1943, Wycliffe Bible Translators officially formed as a separate organization to handle the finances of Cam’s operations.

God Turns Adversity into an Opportunity

Then, in 1945, God laid Peru on Cam’s heart. He and his new wife, Elaine Townsend, traveled to Peru with 19 students. “[The camp in Peru] was like one big, happy family,” Grace Townsend, Uncle Cam’s oldest child, recalled. Here, Cameron became known as “Uncle Cam” because of his friendly personality, a affectionate nickname that stayed with him for the rest of his life.

Translators would go into the jungle to live with the people for weeks to learn their language, and then return to the center in Yarinacocha.

Because these jungle trips were so difficult, Cam increasingly felt the organization needed its own missionary pilots. “There were no roads like [what] we would call roads,” Grace explained. “It would take over two hours to get to the closest village.”

When Grace was six weeks old, Cam took his family to encourage the new recruits at the training camp in Mexico—Camp Wycliffe—where the linguists learned how to live in a jungle.

Their trip to Mexico was uneventful, but their return trip proved to be disastrous. They hired a small commercial plane with no seats other than the pilot’s seat, so Cam and Elaine sat on the floor. Grace was in a basket on their lap.

On takeoff, the tail of the plane hit a tree, and the plane nosedived into the side of a ravine.

“Daddy actually praised God for that accident,” Grace said. “He had proof that we needed missionary pilots.”

Through this difficulty, in which Cam, Elaine, and the pilot all suffered injuries, God provided the impetus for SIL to form a committee in 1948 that later became the organization known as Jungle Aviation and Radio Service (JAARS).

Using pictures of the crash, Cam raised money for the first two airplanes of the JAARS fleet: a Grumman Duck and an Aeronca Sedan, both amphibious—an important feature because most of the people whom SIL was ministering to in Peru lived by rivers.

Stay tuned for the next installment in this series about the early work of JAARS in South America.

For details on our May 12-13 75th anniversary celebration, click here.